“Hey, man, I know it sucks that you can’t smoke in your apartment, but when you do it here, the smoke goes right up into my window.”

This was the first time I met my upstairs neighbor, just over a year ago. I was happily smoking in the alley behind my apartment building, and by “happily,” I mean I was absorbed in my ritual of savoring Turkish tobacco, Colombian coffee and the internet on my phone. I love smoking; smoking offers a few minutes of samadhi as I let whatever I’ve been focused on temporarily float away in the wake of olfactory, chemical and mental stimulation. In these five-minute bursts, my time is my own.

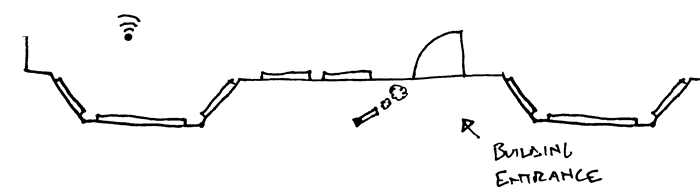

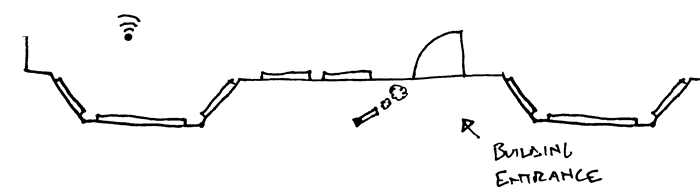

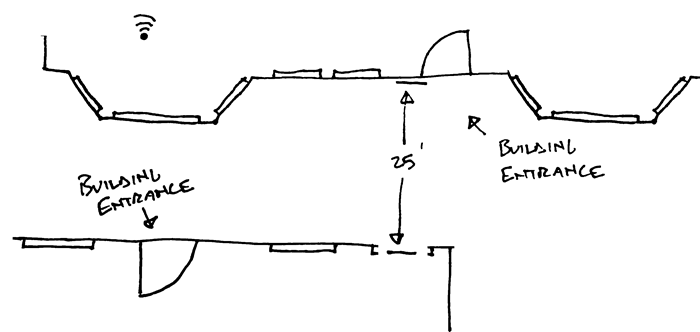

The alley is a convenient location to smoke, because my apartment is on the lower level and my door is just a few steps away from the building’s back entrance. I can stand right outside my own windows, staying connected to my own WiFi with my phone so I’m not running up data charges while passively scrolling through my Facebook news feed as I smoke. I can take my coffee with me (or beer, or wine according to time of day) and set it on my outside windowsill so I can alternate the use of my two hands with three tasks: cigarettes, coffee, internet—the holy trinity of break-time.

When I was 21, I worked in a department store in Kirkland for an amazing Store Manager named Sue. When we’d work together remerchandising the sales floor and would encounter a difficult logistical problem, after staring at it for a while, she’d say, “Let’s smoke on it.” We’d remove ourselves from the problem for a few minutes, have a cigarette on the loading dock, and when we’d come back, the solution would be staring us right in the face. For some people, “rubber ducking” does the trick. For me, “smoking on it” works, and now that I work from home, when I’m too close to a problem to see the solution, I grab a fresh cup of coffee, my phone and a cigarette and head out into the alley for a quick break. I “smoke on it” many times a day. Even more than usual as I write this story about smoking.

My neighbor seemed like a nice enough guy, and he presented his problem in a nice enough way. I felt for him, but in my mind, I was smoking in the neutral zone; telling someone that they can’t smoke in an alley is like telling someone that they can’t smoke in the middle of the damn street. His windows are positioned exactly where mine are, just one floor up, but I don’t try to impose my own rules on people in the alley. An alley, like a street, is utilitarian in nature. An alley is not a flower garden. An alley is not a private driveway. An alley is not a patio (though I used this particular alley very much like my own patio). An alley is a service road. I don’t complain when the garbage truck rumbles through it early in the morning. I don’t complain when cars honk at other cars. I don’t complain when there’s something smelly in the dumpsters, when an amateur drinker vomits on the pavement on a Saturday night, or about the bush that has grown between the two buildings behind me to block my view of the Space Needle over the last decade. I don’t complain when the guy in the apartment across the alley opens his windows and cranks up his stereo. I don’t complain when the carpet-cleaning service parks their truck outside my window and fires up their gas-powered pump to operate their remote equipment inside the building at the end of long hoses. In my mind, my domain ends at the walls of my apartment, so I figured his did, too.

“I don’t know what to tell you,” I said. “I understand what you’re saying, and being a good neighbor is important to me, but I honestly don’t see a solution to to this. I mean, I’m smoking outside, in the alley of all places. I’ll give it some thought, though. I just can’t promise you anything.”

“Well, thanks for listening at least,” he replied, looking dejected. That would be the last time I saw him for a year.

He couldn’t have known it, but I did used to smoke in my apartment. My building didn’t have a smoking policy when I moved in back in 2002. My building manager and I even had a cigarette together in my apartment when he came to go through the punch-list as I was moving in. You’re probably picturing some dingy shit-hole straight out of Trainspotting, but that’s not the case. It’s a beautiful 1906 building that was renovated in 2000—it has regalness and charm, and I’m often inspired to Fred Astaire my way up and down the stairs.

Years later, my building was placed in the care of a new property management company, and they gave us new rental agreements to sign that—though they insisted were identical in nature to our current leases and would not change any of our current terms—simply matched the formatting of all of their other paperwork. I looked through the new documents, and found that they’d slipped in a no-smoking policy. I didn’t sign or return the new contract, so after a couple of weeks, they left another one at my door with the same request to sign and return. I didn’t. They gave up.

Eventually, though, smoking in my apartment became a problem for other residents. Complaints started wafting up to my building managers about the smell of smoke in the halls outside my apartment, and they started giving me warnings. To my knowledge, no one has complained about the acrid scent of my neighbor’s cooking—the smell of tobacco smoke has been given special distinction in the category of things acceptable to revile while we’re still not allowed to fuss about chicken curry. I resisted by ignoring the warnings, but eventually decided not to fight it anymore. Even though I hadn’t signed a no-smoking policy, I didn’t want to be a bad tenant or a bad neighbor; and I certainly didn’t want to give them reason to force me out of the apartment I loved with rent hikes if they didn’t have legal standing on the smoking issue.

Going outside to smoke turned out to be a good thing. It meant that my friends and I couldn’t stand around my kitchen smoking while we drank whiskey or wine like we often did, but we replaced that with a tradition of “a beer and a smoke” in the alley outside my apartment at the end of nights of drinking in my neighborhood. My apartment no longer smelled like stale smoke, I didn’t have to wash my walls and ceilings every couple of months anymore, I wouldn’t have to repaint my apartment again (I’d done it twice), and judging from the stop to complaints, my neighbors were much happier, too. I’ll admit that I’m glad for that kick in the ass. Win-win.

This summer, I saw my upstairs neighbor again, and this time it was a no-more-mister-nice-guy kind of scenario. The warm weather and his love of box fans (seriously, he runs about three of them between his five open windows at all times) steeled his resolve to flush the dirty smoker out from underneath his windows like quail from the bush.

It started with him calling down from his window to ask if we could move away from the building when my friends and I were participating in the “beer and a smoke” ritual. That made perfect sense to me—in this case there were two people smoking, not just one, and we were sucking down cigarette after cigarette while we laughed, talked and drank rather than my normal five-minute smoke breaks. Yeah, I could see how the excess could be a problem, and I’m a reasonable man.

“Sorry, man,” I tossed back up to him, and we moved away. I’d try to remember to keep my gangs of smokers away from the building (I’d even tip off other gangs when I’d see them), though I sometimes forgot and he’d have to remind me by hollering down from his window again. This seemed to embolden him. He approached me in the alley one day with a look on his face like he was one move away from a checkmate.

“You know,” he mused, “you’re supposed to stay twenty-five feet away from the building when you’re smoking.”

“You have a point,” I offered, “I do need to be twenty-five feet from any entrances.” In 2005, Washington State passed Initiative 901 which banned smoking within twenty-five feet of entrances of places open to the public. Also called the Washington Smoking Ban Initiative, at the time, it was the most draconian statewide smoking ban in the country. But I’ve always been fine with the 25-feet rule, just like I’ve been fine with being banned from smoking in restaurants. In fact, I went from acquiescence to to enthusiasm for the ban in restaurants during a trip to Juneau, Alaska.

In 2007, I was in Juneau for ten days to train a new manager in my company. She was from Fairbanks, which like Seattle, had banned smoking in restaurants and bars. On our first night in town, we headed into a little bar above the Thai restaurant where we were waiting for our reservation. Right away, we saw ashtrays scattered around the room, and people using them. Our eyes got wide with excitement. I hunted down an unclaimed ashtray while she got us a table, and we both lit up in utter glee. But, within five minutes, my eyes were watering, my nose was running, and I was miserable. The air wasn’t circulating, so the smoke just hung in front of your face, and I sympathized for the first time with non-smokers who didn’t enjoy my smoking in bars. I’m more than happy to go outside.

So, after my neighbor pointed out the 25-feet rule, I paced off the distance from the doorway, and set my coffee cup on another of my windowsills. Since his apartment is directly above mine, I was obviously still under some of his windows, just different ones.

A couple of days later, he shouted down to move away. There was more anger in his voice than ever before. He’d torn off his screen to allow him to stick his head way out the window to make sure that I could see his face and understand the gravity of his demand.

“Sorry, man, I thought I had moved far enough away,” I called up to him apologetically. So, I moved a few feet further down the side of the building, getting good and clear of his bedroom windows. I’d always been beneath his bedroom, so I assumed his sensitivity centered there. I was still below his living room windows, but in my mind, he could close those and still get plenty of air in his apartment through his bedroom windows. The apartments aren’t large, after all. He could keep half of his windows closed, and I could stay thirty feet from the entrance. It seemed like a good compromise.

This situation lasted about two days. I was on a smoke break when my neighbor decided to take out the trash. As he was coming back toward the building, he stopped in front of me with his hands on his hips.

“You know, three feet isn’t much of a concession,” he barked.

“What?”

“Three feet isn’t much of a concession. You moved from right there to right here,” he said, pointing at spots on the ground where I have stood smoking, “and you think that’s going to do it?”

“Look, I’m done,” I said, exasperated. He smiled like he’d won. “I’m done trying to appease you,” I continued. He stopped smiling. “I used to smoke over there,” I pointed toward the door, “and you said I had to be twenty-five feet away, so I moved. That wasn’t enough for you, so I moved even farther down, but nothing can satisfy you, so I’m done.”

“Why should I have to smoke your cigarettes?” he asked. This was a clever framing of the issue, I’ll admit, one that he probably picked up with browsing thetruth.com in the middle of the night. When smoking was first banned from bars and restaurants, two lines in two newspaper stories had gotten me on board. The first was, “The risk of lung cancer should not be a job requirement.” The second was, “A smoking section in a restaurant is the equivalent of a peeing section in a public swimming pool.” When you put it that way, I totally get it. This guy was suggesting that I was forcing him to smoke my cigarettes, which is clever, but it’s not quite the same. After all, he could always just close his windows. You can’t do that in a restaurant.

“Why should I have to take a walk?” I retorted.

“It might do you some good!” he said, as if the suggestion that I could use the exercise would change my opinion on the matter. “Hey, my wife smokes,” he said, trying to establish his credibility, “but she has the courtesy to do it away from the building.”

This last bit simply told me that he wasn’t suffering from some sort of allergy. He was just sensitive to smell. Well, he could always close his goddamn windows.

“It looks like we’re at an impasse,” I told him, “It’s your comfort versus mine. I’ve already made several concessions, so now it’s up to you.”

“Look,” he said, “six months out of the year, I don’t care if you smoke out here, but when the weather is nice enough to have my windows open, why shouldn’t I be able to do that.”

“Six months?” Half a year isn’t a minor thing.

“Man, that’s why there are rules,” he said.

“Which rules?”

“The rule that you have to be twenty-five feet from the building when you smoke. They’ve put out a bunch of memos about it.”

“You mean twenty-five feet from the entrance, and I’ve already done that. I’m actually thirty feet away.”

He threw up his hands and stormed off.

I don’t especially enjoy pissing people off, and it’s certainly not my mission to make other people’s lives uncomfortable. While my neighbor and I had clearly just reached a Hatfields-and-McCoys level of disagreement, I didn’t want to be the asshole in the situation. Was there a reasonable accommodation to be made on my part? If I moved down the side of the building in the other direction, I’d be standing under someone else’s windows. If I moved to the other side of the alley, I may satisfy this neighbor, but I may be pissing off someone else. In fact, that wasn’t even possible, because the building across the alley was just shy of twenty-five feet away (I measured). So, my neighbor wanted to control the behavior of people in the whole alley? This was just too much.

I’d like to emphasize that I’m not an unreasonable guy. I’m not even habitually inconsiderate. When I got a new neighbor across the hall from me a few months ago, she started having people over after work on Friday or Saturday nights. Since she works in a restaurant, this meant that she and her co-workers would gather in her apartment really late at night and drink until dawn. They’d go out the back door to smoke and stand right next to my bedroom window, shouting and laughing and engaging in horseplay until the sun came up, robbing me of any chance at sleep. Since there were a bunch of them, the noise didn’t come in bursts, but continued for hours as party-goers came in and out in a rotation. By 4:30 in the morning, I gave up trying to sleep and had a talk with them. They were all really nice, and really apologetic, but they were drunk and didn’t know how to use inside voices when they were outside, even though it was the middle of the night. After two or three weeks of this, I talked to my neighbor directly. She was really nice about it, too. I told her I understood where she was coming from, and that I wasn’t telling her not to have parties. I just asked if she’d tell her friends to quiet down a little after 2:30 in the morning. She told me she understood completely, admitted that while it was happening she was too drunk to care, and gave me permission to either come yell at them or join them if they were ever making too much noise. I thought moderate noise control after 2:30 a.m. seemed a reasonable compromise, and it was actually never a problem again.

I started analyzing my neighbor’s problem. I tend to think that with a little rationality, a workable solution can be found that makes both parties happy in a conflict. Maybe he could close half of his windows, and I could stand under the closed ones. Maybe there were certain times of day when he really wanted his windows open (during the hottest times of day, or during the coolness of evening?), and during those times I could move further away but be able to smoke where I wanted to during the remainder of the day. Maybe we could negotiate something around his work schedule. But my upstairs neighbor wasn’t interested in compromise. He was on a crusade. He was playing an all-or-nothing game.

In my mind, when you open your window, you are inviting the outside in. If it’s too cold, too noisy, or too smelly, you close your window again. It’s very simple. This guy, however, wanted all of his windows open all the time (day and night), and wanted dictatorial authority over the quality of the air he was sucking into his apartment with myriad box fans. He didn’t just want control of the inside of his apartment—he could close his windows for that—he wanted control of the outside, too. Is there anything more selfish?

And this was the rub. I’d reluctantly embraced the prohibition of smoking in my home. I’d happily accepted not being able to smoke in restaurants and bars. I didn’t make a stink about having to further remove myself by another twenty-five feet from entrances. I’d paid without grumbling when numerous “sin taxes” were added to the price of a pack of cigarettes. I’d even woefully accepted it when my building decided not to allow smoking on the rooftop deck for fear of fire hazard—no more lazy summer nights with friends relaxing on the roof overlooking the city with a bottle of Prosecco, a guitar and a pack of delicious cigarettes. But now, some guy was trying to tell me that I couldn’t smoke outside in open air on public property just because he refused to keep the option of closing his windows on the table. That’s just too much to accept.

Smoking has been falling out of fashion for a couple of decades, though there have been spikes in some demographics recently. As one old man wheezed to me while borrowing a lighter, “We’re a dying breed.” And among the growing numbers of non-smokers, plenty of them support various smoking bans for a few reasons. There’s the health issue, sure, and the economic impact of droves of people flooding hospitals with lung cancer every year. But, the loudest of those who want to limit smoking do it because they personally just don’t like the smell of smoke—they think it’s gross. They’d be happy as clams if no one was allowed to smoke anywhere near them ever.

In my view, this would be like me saying that I hate the smell of fish (which I do, it can literally make me nauseous), so no one should be able to cook or eat fish anywhere near me. Oh, you say, you can’t tell people that they can’t eat fish! Fish is good for you! Everyone likes fish! Fish isn’t the same thing as a cigarette! Well, this is a value judgment, and we can disagree on the merits of both fish and tobacco.

My upstairs neighbor has a little dog. I know because I can hear it scamper around his apartment late at night. I can also hear it throw its own ball and then chase it as it bounces across the hardwoods. It has woken me up from a dead sleep a bunch of times, and despite the fact that my building has a no-dogs policy, I’ve never complained. Oh, but dogs are adorable, so they’re OK, you might say. Again, this is a value judgment. His lifestyle affects me, but I don’t complain. My lifestyle affects him, and he’s going to freak out about it like a little bitch. The difference is that when his dog is waking me up, I can’t just close a window. Another difference is that my actions are taking place outside of the building on public property.

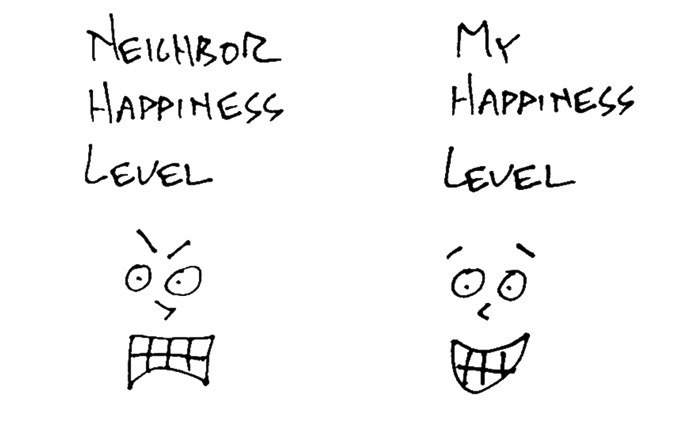

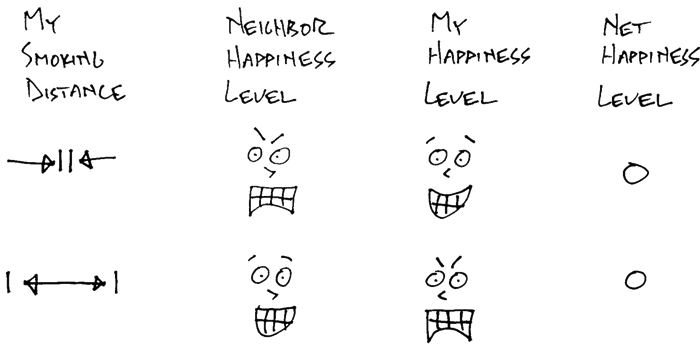

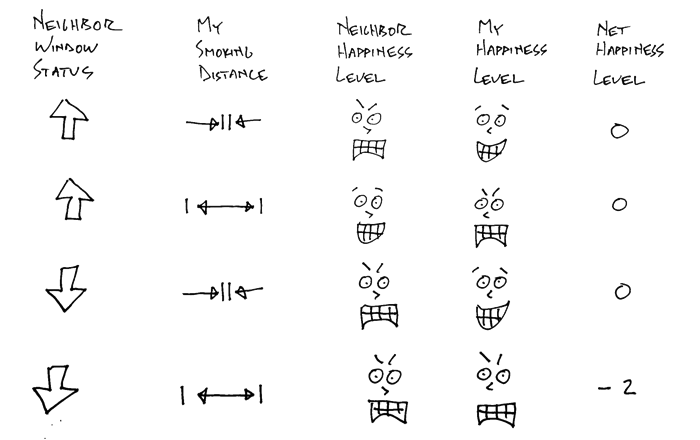

So, the smoking debacle was a zero-sum game. It was either his happiness or mine, and if those are the only two options, I was going to choose mine. I thought of it in terms of a Smoking & Happiness Chart.

The next morning, when I went outside with my coffee for my first smoke break, I noticed some graffiti on the wall of the building. In white chalk, with big nine-inch letters, it said

This is NOT

the SMOKING

area!

The guy was going bat-shit crazy! When all else fails, vandalize the building. That’ll do it. Or, in the event that I may not have seen it as vandalism, I may have mistaken it for an official notice, and shuffled away in order to be in compliance. Who fucking knows what he was thinking. I went back inside and filled a bucket with soap and water, grabbed and scrub brush, returned to the alley and cleaned it off. If I were more disputatious, I would have taken a picture and shown it to the building managers, but I didn’t. I just thought this was the desperate act of a desperate man who could only see failure in compromise. I wasn’t about to feel sorry for Napoleon for losing Leipzig.

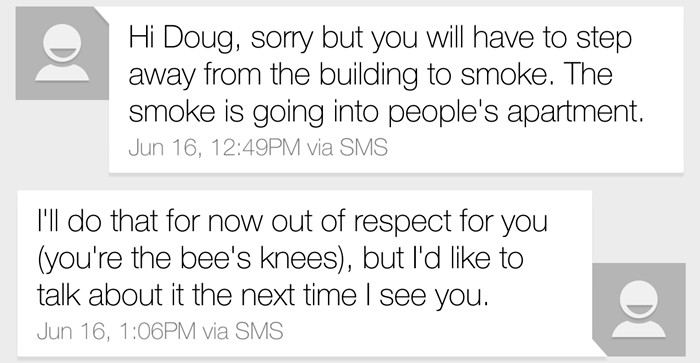

He wasn’t done, though. After I carried on as usual that morning, I got a text from one of my building managers in the early afternoon.

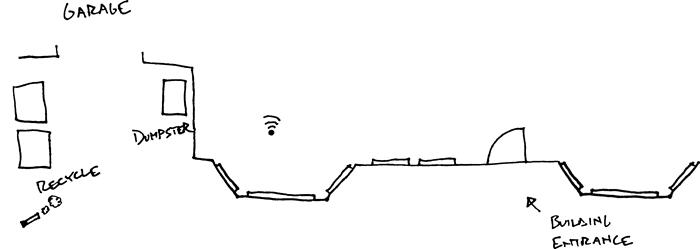

So, he’d filed a complaint with my building managers. I felt bad that they had gotten dragged into this. Veronika and Sam are really great; they’re genuinely nice and they do everything they can to make the tenants happy. I’ve always had a great relationship with them, shot the breeze with them, laughed with them, and they’ve even played practical jokes on me that were hilarious. Now they were trying to make my asshole neighbor happy, though I’m sure he was nice as can be when he asked them to intervene. I’m sure he didn’t tell them about his graffiti either. I didn’t want to call them and start whining like this guy had. I didn’t want this whole thing devolving into little kids crying to their parents from the backseat of the car about who was touching whom. I was sure that they’d see the logic in my position and land on my side of the issue, so I agreed to temporarily suspend my ritual of smoking next to the building until I could explain the situation to them in person, though I was none too happy about it. Moving further away meant that I had to stand next to the dumpsters like a fucking juvenile delinquent in high school.

That afternoon, a memo was slipped under my door. I don’t know if my building managers put it there, or if my upstairs neighbor had slipped me one of the many copies he’d said had been distributed.

The memo did indeed state that tenants aren’t allowed to smoke within twenty-five feet of the building, and that failure to comply could result in a ten-day notice to evacuate. It gently asks that tenants tell their visitors also not to smoke near the building out of courtesy.

This policy made no sense to me. How could the building enforce a rule about how tenants behaved outside of the building—a rule that could not be enforced on anyone who’s not paying rent? I was now as obsessed as my diabolically crazy adversary. I walked over to the street side of the building, and measured twenty-five feet, which put me in the street. The sidewalk wasn’t even a safe distance. I went to the front of the building, and again measured the distance, again landing in the street. Somehow, they’d banned smoking inside the apartments, on the roof, and now within a perimeter around the building, creating a three-dimensional smoke-free bubble.

I couldn’t think about anything else. I mulled it over and over, trying to maintain a view from the 30,000-foot level. I didn’t just want to win the argument, I wanted to be on the right side of the argument. It wasn’t so much about my own inconvenience as it was about justice. I committed to staying rational, I tried to be objective and I looked at it from every angle I could think of. If I were Solomon, I would have ordered that baby to be cut in half.

My neighbor didn’t like my cigarette smoke, but I didn’t like smoking near the dumpsters. Not only is it less convenient, but it’s right in that sweet spot (or sour spot) where I just get enough WiFi to keep my phone from switching to the network, but not enough for my phone to function on the internet. I have to manually turn off my the WiFi on my phone, and then run up my data. It’s also just unseemly to set my coffee cup on top of the food waste bin, and I’m more exposed to the rain when it’s coming down. Still, was I really in the right here?

It suddenly occurred to me that there was something I hadn’t considered in my initial look at Net Happiness. If I was smoking near the building, I was happy and my neighbor was not. If I was smoking away from the building, my neighbor was happy and I was not. But, both of these scenarios presupposed that his windows were open. If he could close them, there were two more scenarios to add.

Looking at it this way, it was no longer a zero-sum game. I realized that his actions of opening or closing his windows had absolutely no impact on me, while my actions of smoking near or far from the building did have an impact on him. If I smoked near the building, he had a choice of closing his windows (unhappy) or opening them (unhappy), so there was no good alternative for him. But, other than yelling at me, none of his actions were making me unhappy. Whether his windows were opened or closed, my cigarettes and coffee were just as delicious. I was the only one doing something that affected the other. This means that when you consider all four possible scenarios, there’s a Net Happiness Level of -2. Not good at all.

It was this realization that caused me not to resist the ridiculous memo, and to stop ignoring my neighbor’s wishes. I still think he’s a selfish dick, for sure, and I doubt we’ll ever have a convivial exchange of words, but I was the one being a bad neighbor. I’ll go on hating him, and he’ll go on hating me, but he’ll have fresh air, and I’ll have the satisfaction of taking the high ground. Maybe I’ll declare war on his dog, or maybe I’ll start calling my building managers to complain when he’s hammering on shit like he’s started a business assembling IKEA furniture from home. Or, maybe I’ll just let it go, and continue to find samadhi from a distance.

Sometimes you have to be the bigger man, especially when you’re left with no other options.